Tensions in France

December 15, 2020

Earlier this year in October, a teacher in a suburb of Paris was decapitated by a Muslim refugee for showing his students a cartoon. The same cartoon was shown in an article five years earlier by the French newspaper Charlie Hebdo, where 12 people were murdered by two Muslims shortly after it was published. Why? Because they depicted Muhammed, the founder of Islam, often disrespectfully, which in itself is considered highly blasphemous to most Muslims. Shortly after Charlie Hebdo published it, France was forced to temporarily close over 20 embassies and schools in many Muslim nations, who in turn boycotted French goods, gaining the attention of the rest of the world.

But French officials looked at this issue as a terrorist attack, and not only allowed those caricatures to be republished, but some went further – including a few who announced they would distribute booklets containing those caricatures to high school students. These moves, however, only proved to make matters worse, having turned France’s people against each other.

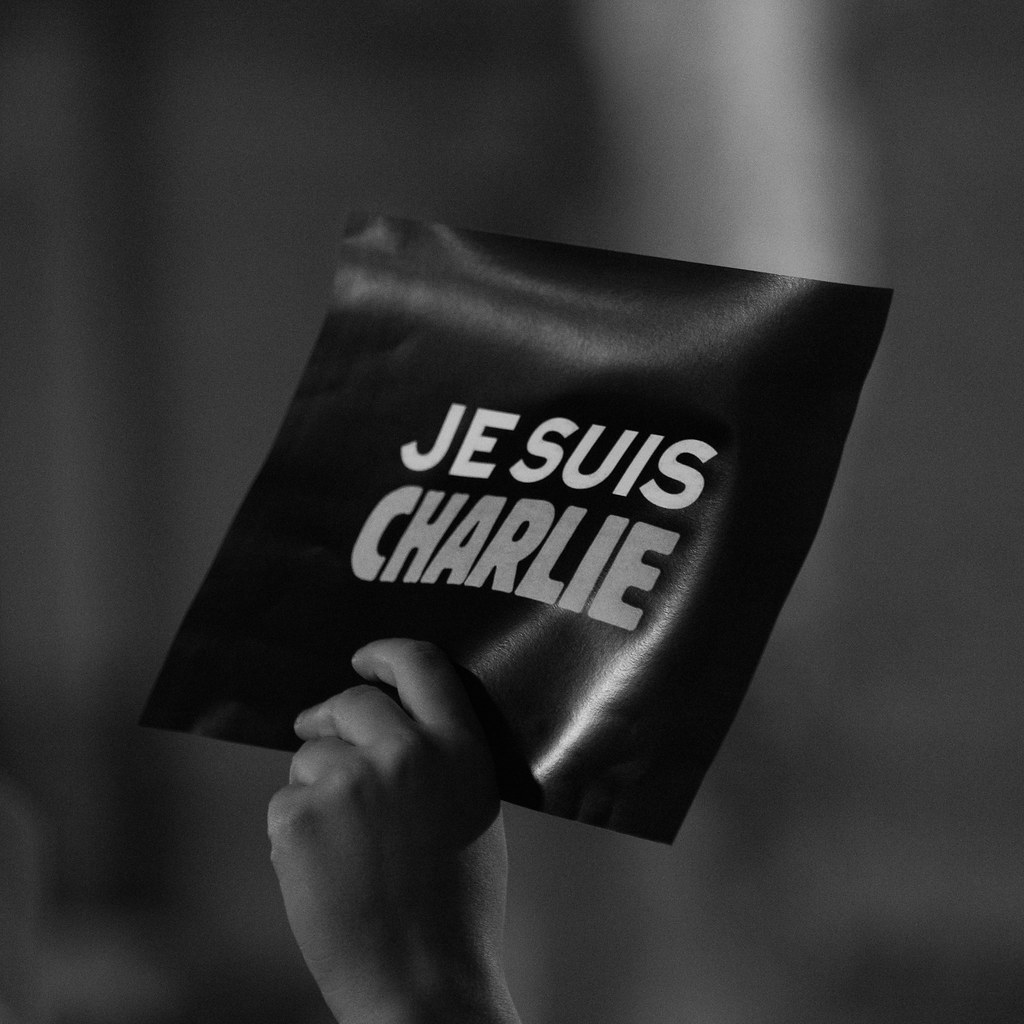

Many countries, including the U.S., have even advised France against going further. Not long after the beheading in Paris, three more people were killed by a Muslim immigrant from Tunisia, this time in the main Basilica of the French city of Nice. Shortly after, what began as a gathering of 50 people mourning for the loss of the dead turned into a full-scale protest that blamed Islam for the attack. The mayor of Nice openly supported the protests, claiming, “We’re at war, against an enemy both inside and outside.” These attacks, especially the one on Charlie Hebdo, led to massive protests throughout France, in which protesters held signs that said “Je Suis Charlie” or “I am Charlie.”

The republication of the pictures also caused massive opposition, especially after French President Emmanuel Macron gave a powerful speech explaining that he would do what he could to crack down on “Islamism.” This proved to have a negative effect and changed the perspective of many people who used to support that cause. In response to the speech, Anne Giudicelli, a French expert on the Arab world, claimed, “The publication and republication are not the same thing.” Also, in response to the speech, a Muslim murdered two people protesting outside the Charlie Hebdo offices and another murdered another teacher showing depictions of Muhammed, including one showing him naked on all fours.

Freedom of expression has steadily become a pillar of France’s secularism, or laïcité. But is it appropriate to oppress religion just because it opposes secularism?

Freedom of expression has steadily become a pillar of France’s secularism, or laïcité. But is it appropriate to oppress religion just because it opposes secularism? France also has laws preventing discrimination against someone’s race or religion, but many officials seem to have turned a blind eye to it.

As French politician Clémentine Autain puts it, the debate over terrorism and secularism “is dominated by emotion and is no longer rational.” Both sides are becoming more and more radical on the issue, and she claims French officials are using it as a way to “ostracize Muslims.” On the other end, Muslims are using it as a way to protest France’s opposition to religion and oppression of people who violate their meaning of “freedom of expression.” But really, what does “freedom of expression” mean? Both sides have their own meaning of it, causing this issue to escalate to what it is today.

Currently, 14 people accused of helping the Charlie Hebdo murderers are being tried in court, which started on September 2nd of this year. This issue, clearly, is far from over.