Bitcoin, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Blockchain

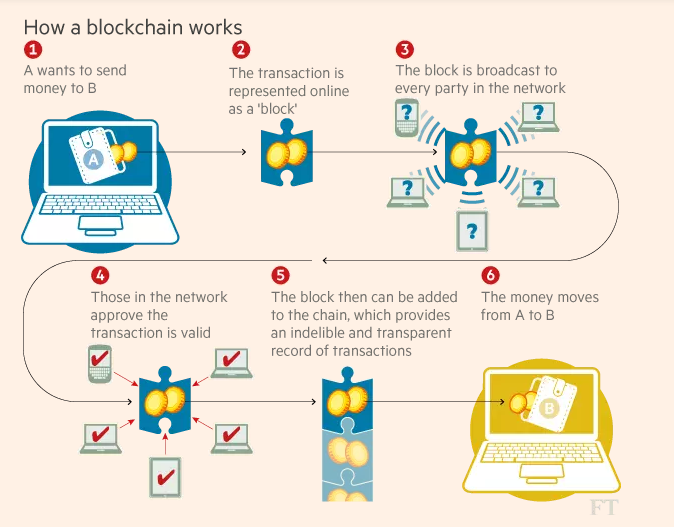

Photo Credit: Jane Wild, Martin Arnold and Philip Stafford via Financial Times

This graphic explains how Blockchain transfers money from A to B

February 9, 2018

Bitcoin never fails to leave investors, speculators, and average Americans alike stunned by the speed and volatility of the cryptocurrency market. Yet, the currency’s nebulous future, coupled with over-hyped present-day news coverage, overshadows its equally nebulous past. The craze that gripped online markets began 9 January 2009, with a white-paper titled “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System” written by a certain Satoshi Nakamoto, a pseudonym. It didn’t take long before Bitcoin took off and Nakamoto, identity unknown, vanished.

Bitcoin wasn’t wholly new, however, as digital currencies had been tried before, but was important as a case study for a new kind of data storage system known as blockchain. A relatively obscure accounting practice never widely used, the concept of the blockchain itself had been around since 1991, when two researchers published the system in the Journal of Cryptology. Nakamoto’s use of blockchain solved many problems plaguing the cryptocurrency market, but also solved another problem in the world at large: how to keep track of stuff cheaply, securely, and quickly.

Blockchain is a mélange of recently developed cryptography, networking tech, and algorithmic advances that are used to create a ledger that manages itself. For example, if you, Adam, wanted to give money to Sally, a bank would have to verify your transaction, update you and Sally’s account balances on their master ledger, which is overseen by an army of accountants, and take a potentially hefty fee for its services. A blockchain, by contrast, uses modern cryptography and peer-to-peer networking to quickly and securely update a world-wide ledger, and give individuals a small fee for the work required to maintain the network. It eliminates the need for most, if not all, modern accounting work, and at a certain scale, eliminates the need for banks as a whole.

A transaction within the blockchain starts with what’s called a block. Inside each block is a group of transactions individuals made to others, like “Adam transfers Sally $10.” Next, someone called a miner will compute a unique identifier for that block called a hash, that makes sure each block is different and tamper-proof. The miner, in return for his services, gets a small amount of Bitcoin. Once that hash has been computed, the miner will broadcast that block with the unique hash across the network. Then, each person on the network will find the block with the most computing work and the most miners working on it, and add it to their blockchain, hence the name blockchain. They link the new blocks with the old ones in a chain so that it’s impossible to change the history of transactions, or else a hacker or fraudster would have to recalculate the unique hash of every single block before his new one. This makes sure that both the currency can’t be duplicated and that everyone has the same ledger across the network. Once everyone has the same ledger, the process continues, moving onto the next block, completely devoid of any accounting work.

The net effect of a network like this is that trust, practically a commodity today, is completely out of the picture, and management, a necessity, is handled algorithmically by the ledger itself and the people using it. But, blockchain can be used for anything that involves transactions: inventories, employee data, loan processing, court cases, voting, and every other sector that involves some kind of central ledger. All those areas that were previously expensive to manage, prone to human error, and vulnerable to attack are now easy to protect, update, and use. Banks today have started to use the technology to eliminate middle-management and accounting jobs, starting small-scale deployment saving up to $20 billion dollars, according to Santander. By putting an algorithm in charge, people ironically have more control of their money.

Far from the court intrigue around Nakamoto’s rise and disappearance, the explosive rise of Bitcoin, and the subsequent ire of trade regulators awake at night, blockchain alone has the potential to reshape the world economy’s financial backbone. Modern banking, with blockchain behind it, has almost solved the age-old problems of trust with distrust, trade with isolation, security without vulnerability, and speed without sluggishness. The future of banking lies not with Bitcoin, but blockchain.